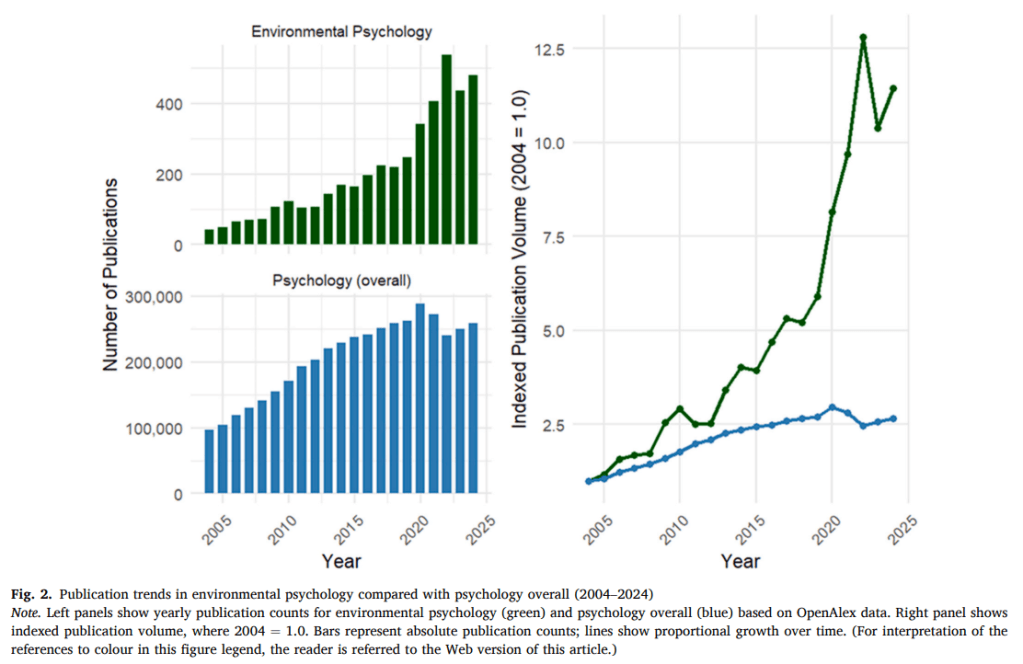

Over the past two decades, environmental psychology has grown rapidly, but there has been little systematic work mapping what the field actually looks like at scale. In this paper, we set out to take stock of the literature. To see where we’ve come form and see where we’re going.

Using bibliometric methods, we analysed 4,313 peer-reviewed publications from 2004 to 2024 drawn from core environmental psychology journals and from articles where authors explicitly identified their work as environmental psychology. Our aim was not simply to count papers, but to understand how topics cluster together, how collaboration patterns are structured, and how the field has evolved over time.

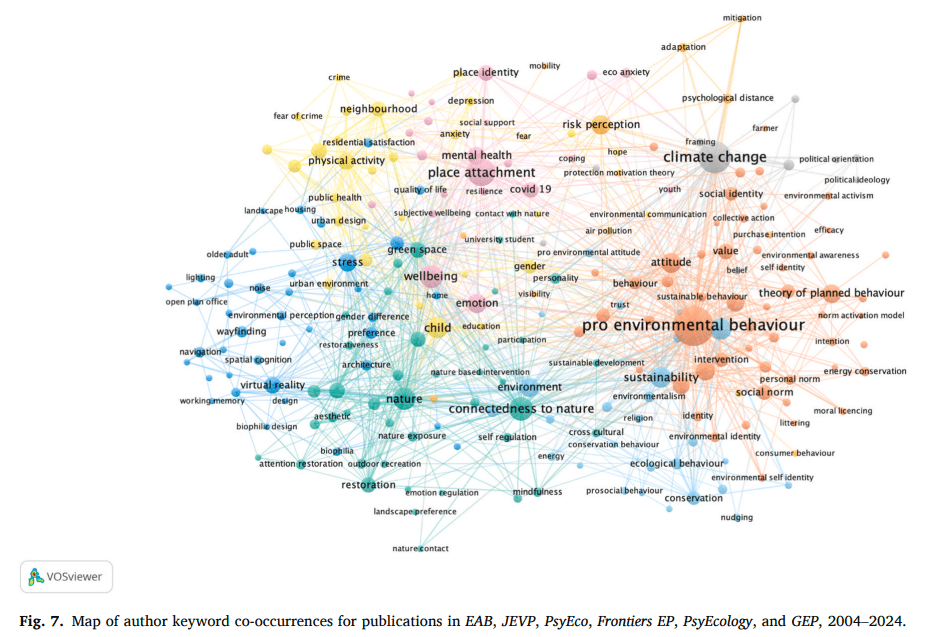

Using VOSviewer network mapping, we examined co-authorship networks, country collaborations, and author keyword co-occurrence. The keyword analyses revealed eight broad thematic clusters that define much of contemporary environmental psychology: human–nature relationships, children’s environments, virtual environments, pro-environmental behaviour, neighbourhood and built environment, place attachment, stress and wellbeing, and climate change. Over time, we observed particularly strong growth in research on pro-environmental behaviour and climate change, while topics related to the built environment became less visible as distinct clusters.

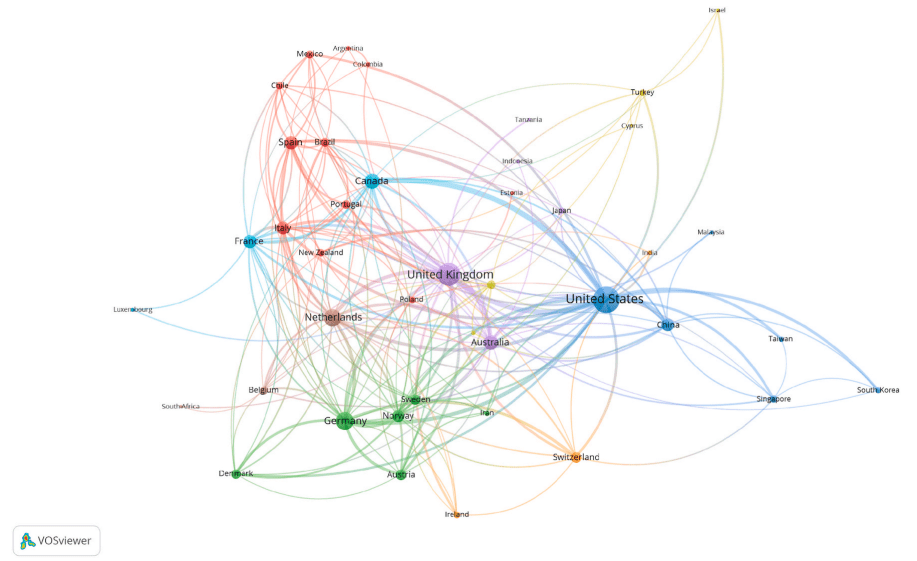

Co-authorship mapping also showed that research activity tends to cluster around specific topics, with relatively limited crossover between topic communities and between authors in the Global North and South.

Importantly, we also highlighted what is less visible. Despite environmental psychology’s historical engagement with built environments and social ecology, we found relatively little emphasis on conflict, migration, ageing, or deeper engagement with cultural and Global South perspectives. Collaboration networks were dominated by the UK, US, and Western Europe, with sparse representation from much of Africa and other regions. These gaps matter because the environmental challenges shaping the next decades, including climate displacement, urban heat, biodiversity loss, and inequality, demand perspectives that are global, interdisciplinary, and attentive to structural differences.

We tried to make this paper both descriptive and reflective. We show a field that is expanding rapidly and coalescing around sustainability and climate action, but also one that risks thematic silos and geographic concentration. By visualising where connections are strong and where they are thin, we hoped to provide a resource for collective self-examination. Environmental psychology has enormous potential to contribute to urgent societal challenges. Mapping where we have been is one way of thinking more strategically about where we might go next